Some Speculations

Language study carried out by India's linguists under the rubric of Vaiyyakaranas (वैयाकरण), like several other vidyas (विद्या) has an ancient pedigree in India. In fact only two ancient civilizations theorized about language- the Greek and the Vedic/Hindu. However, the two are different in their focus, their growth and history which springs partly from geo-history and partly from civilizational difference between 'the Geometry people' and 'the Vaak-people' between the scriptal and the oral people. The Greeks thought a good deal about the sacred alphabet, sparsely about the language of literature, discourse and rhetoric (Aristotle primarily). Plato in his Cratylus speculated about the difference between speech and writing. But there is an absence of systematization and continuity may be because the Greek civilization did not last very long situated as it was on the cross roads and collapsed between the Romans and the Persians. Aristotle’s parts of speech in Poetics show the elementary stage of the Greek understanding of the structure of language. But the Vedic/Hindu history of ideas is uninterrupted, continuous and cumulative and shows a systematic growth and development for, to put it conservatively, more than 3000 years.

Right from the Rgveda (ऋग वेद) itself, the Indian mind has reflected continuously on the

nature and structure of language. The

Sanskrit grammarians did total thinking about language from phonetics to

philosophy and in the process, as has been noted, had gone to the sea-shore in

search of cowrie-shells (sounds of language) but ended up by finding a pearl (sabdabrahma- शब्दब्रह्म).

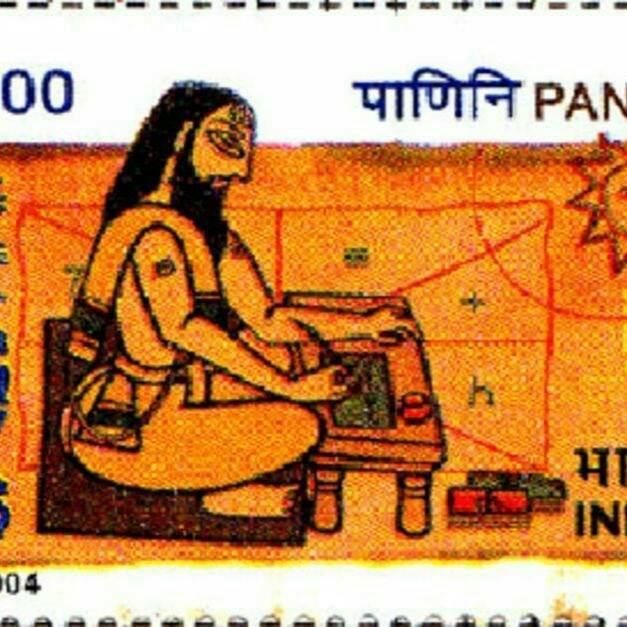

Panini the Grammarian is a watershed in the

linguistic history of India -- there is before-Panini linguistics and there is

after-Panini linguistics. The long history of thinking about language can be

divided, for convenience, into five phases of development from the Pre-

Paninean period to our times. The first

phase is a long period from the Rgveda

to Panini (7th century BC) marked by extensive reflections on

different aspects of language in both non-linguistic texts such as Vedas and

Upanisads (उपनिषद) and (some of the available) directly linguistic texts such as Yaska’s

Nirukta (निरुक्त), Dhatupathas (धातुपाठ) and possibly some Pratisakhyas (प्रातिशाख्य).

All the three words used for language, bhasa (भाषा), vak (वाक्) and vani (वाणी), point to

the sound substance of language, that is, language is speech. Bhasa is from the verb-root bhas (भष), which means ‘to make sound/noise’;

vak is from the verb root vac (वच), which means ‘to say some thing’; vani is from the verb root vanj (वंज), which means ‘to say something

sweetly’. The most significant effect of

this assumption was the rise of phonetics as the first science in India and the

sophistication of phonetic analyses achieved in the tradition. Panini’s grammar

is also founded on this assumption

Pre-Panini period was the phase of phonetics, etymology, lists/lexicons and morphology. During this long period Phonetics was the first science to develop in response to the need to preserve intact, to articulate accurately and to transmit exactly the Vedic mantras. The phoneticists’ chief contribution, however, and one that contributed significantly to the science of grammar is their hard, precise analysis, description and classification of speech sounds on the basis of place and manner of articulation and their description and classification of process and principles of sound change in context. This had enabled Yaska the etymologist to account for language change - in the sound shape of the form in the course of its derivation from the root, dhåtu to the final form (Nirukta I). Their work, and that of Yaska, is the foundation of Panini’s morphophonemic description of Sanskrit. Further, the phoneticists’ structural analysis of speech sounds as bundles of phonetic features made possible the prayahara sutra, the pratyahara (siglas) and the sophisticated sandhi-rules (morphophonemic rules) of Panini’s grammar.

Thinking about language originated in the Vedic literature with its innumerable reflections on sabda, language, its nature, its constitutive elements, and its relationship to the mind and the reality it talks about. It is asserted that life-breath and mind are the two roots of speech. The second Aranyaka describes prana (breath; conscious and unconscious energy that supports life) to be at the root of speech and designations, on which the knowledge of the whole universe rests. The relationship of inhaled, life-supporting breath and speech (language) comes in for more reflection. The third Aranyaka tells us that Kauntharva saw a union of speech and prana --“vak pranena samhita iti kauntharva” (III.1.6). (Excerpts quoted from Kapil Kapoor's Article on (Paradigm Shift in Indian Linguistics and its Implications for Applied Disciplines, IIAS, Shimla, Nov 2017)